Items related to A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle...

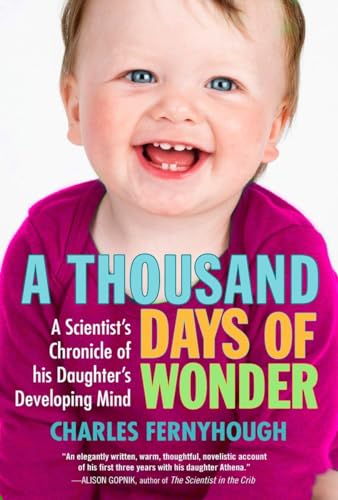

Unlike any other time in our lives, we remember almost nothing from our first three years. As infants, not only are we like the proverbial blank slate but our memories are like teflon: nothing sticks. In this beautifully written account of his daughter's first three years, Charles Fernyhough combines his vivid observations with a synthesis of developmental theory, re-creating what that time, lost to the memory of adults, is like from a child's perspective.

In A Thousand Days of Wonder, Fernyhough, a psychologist and novelist, attempts to get inside his daughter's head as she acquires all the faculties that make us human, including social skills, language, morality, and a sense of self. Written with a father's tenderness and a novelist's empathy and style, this unique book taps into a parent's wonder at the processes of psychological development.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteeen

Sixteen

Acknowledgements

Notes

Index

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin

Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL,

England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin

Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria

3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt

Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India Penguin Group

(NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson

New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Originally published in the United Kingdom by Granta Books 2008

First published in the United States by Avery 2009

Copyright © 2008 by Charles Fernyhough

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed

in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate

in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights.

Purchase only authorized editions.

Most Avery books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs. Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Special Markets, 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fernyhough, Charles, date.

A thousand days of wonder : a scientist’s chronicle of his daughter’s

developing mind / Charles Fernyhough.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN : 978-1-101-02930-5

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Squiggle and for Cherry

One

IT’S LIKE THIS

Remembering a Beginning

I didn’t know where to start, so I asked her.

“Athena?”

She was feeding me coffee dregs from a teaspoon. It was a cold, bright midmorning in June, and the shoppers had abandoned central Sydney to the part-time dads and a few hurrying office girls. We were sitting in a café on the first floor of the Queen Victoria Building, feeling the winter draft from the nearby escalator. She was nearly three.

“Do you remember being a little baby?”

“No.”

“Do you remember anything about being a baby?”

“No.”

She continued scraping the teaspoon around the rim of the empty cup.

“More? More?” she offered. “Shall I feed you?”

I leaned forward obediently. She dug deep with the spoon and scraped another bit of metallic-tasting coffee scum into my mouth.

“When you were a little tiny baby, what was it like?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know yet.”

Yet. Was it all about to come back to her?

“Can you remember some of the things we used to do?”

“Oh, you always say that,” she sighed.

I sat back, a little surprised by my daughter’s tone. As I studied her determined, slightly cross-eyed scouring of my coffee cup, I wondered whether I had really asked this question before. I had probably come up with some that were equally impossible, and possibly equally absurd.

“That’s because I’m interested.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s interesting. Because you’re interesting.”

She clattered the teaspoon into the saucer. “Now you be the clapper and I’ll be the pig!”

“Can you remember?”

“Clap! You have to clap!”

I clapped. Office workers hurried past with plastic-lidded cappuccinos, bemused by the applause from the Old Vienna Coffee House.

“Athena, when you were a little tiny baby, what sort of games did we play?”

“Well,” she replied, with somber certainty. “I think we used to play chaseys.”

“What about before you could run around, when you were still a little tiny baby? Can you remember what it’s like to be a little tiny baby?”

She pulled the straw out of her orange juice and trumpeted at me through it, spattering me with its sticky warmth. I felt a faint, familiar despair.

“Can you remember who looked after you when you were a little baby?”

“Mummy.”

“Who else?”

She looked up at me with the straw still bitten between her teeth. Wisps of blond hair curled into the corners of her eyes. Her blue irises were big and clear. My questions seemed to bounce off her. They were just the latest stuff being shot at her, to be dodged or endured. But I needed her answer. Something extraordinary had happened to our yowling newborn of nearly three years ago, and she was the only true witness to it. I had observed her transformation from the outside, documented her emergence into this flitty center of experience with which I could, with a little prompting or bribery, have a tentative conversation. But she was the only one who had lived through it. I had my notebooks, my jottings and theories, but careful observation would only take me so far. I needed my subject to remember it for herself.

Then she smiled. I like to think she smiled.

“Daddy,” she said.

Looking back, I realize that I was asking a lot of a child so small. If Athena had been like me, or just about anyone else who has ever been asked the question, she would have been able to recall very little detail about the first two or three years of her life. No matter how you choose to quiz people about it, no one seems to have demonstrably accurate memories of their very early childhood. On the face of it, young children aren’t just a blank slate, a tabula rasa—they’re a nonstick surface. The events of life do not cling to them. There has not, Sigmund Freud once observed, been enough astonishment over this fact.

Psychologists have recently begun to make progress in understanding why memories of our earliest lives do not stay with us into childhood and beyond. One thing we know about memory is that different kinds of information are organized in different ways. Information about facts goes into one system, known as “semantic” memory; information about events that happen to us (our “autobiographical” knowledge) goes into another. At nearly three, Athena was already skilled at handling certain kinds of facts about the world, such as her date of birth, or the fact that the first train stop after the Harbour Bridge was Wynyard. But her capacity to organize her knowledge of things that had happened to her was only just beginning to develop. She was not yet an autobiographer. Her own life story was not, for her, a proper topic of study.

Perhaps that was because handling information about your own life requires something more than the retention of impersonal, objective bits of knowledge. To say that you possess semantic knowledge of, say, the capital city of a particular country, it is enough simply to know the fact: you don’t need to recall the specific instant when that information became known to you. But when it comes to the details of our own lives, that personal, subjective quality is the essence of what we remember. It was not that Athena found it impossible to process facts about her own past. She had prodigious memory for various kinds of autobiographical information, such as promises we had made her in weak moments, or the clothes she had been wearing when she visited a certain place. But she couldn’t re-create the visit itself; she couldn’t put herself at the center of the recollection. In fact, memory researchers are now suggesting that this special, subjective aspect of memory may not start to develop until halfway through the third year of life. If this is true, then it would explain why our earliest years are a blank for most of us. In infancy, we are absent from our memories. We can live, but we cannot yet relive.

What are you writing?” she asked.

I looked up from the crowded pages of my notebook. I’d been unaware that, once again, my observations of the thing had distracted me from the thing itself.

“I’m writing down what you say. I’ve been writing down all these notes since you were a baby.”

“Why?” she said, looking faintly shocked.

“Because that’s what Daddy does. He tries to understand how little children think. That’s his job.”

She laughed at that. Daddies stared at blank pieces of paper all day and then went for long walks, talking to themselves. That surely couldn’t bring you to an understanding of anything.

“You know what?” she said, obligingly. “When I were a little baby, it were very sunny.”

I nodded, trying to coax the thought into the open. I suspected that this summery recollection had something to do with the previous year’s family holiday, but it may only have been the afterglow of the home movies we had recently been watching. Athena’s grip on the memory was unsure, and I could understand why. If she had only begun to center herself in her memories at two and a half, then fivesixths of her life was forgotten. How did it feel, to have so much of your past immediately lost to you? Was life still a blooming, buzzing confusion, a movie in which she had only just begun to star? What was it like for her?

I had a particular interest in that question. I had studied children’s development in the abstract, from a safe academic distance, for all my years as a graduate student and then part-time university lecturer. I had seen how much profound change happens in the first three years of life, in just about every aspect of a human being’s psychology. Within a few years of her birth, a newborn baby has to build a mind out of chaos, gain control of her own actions, acquire the ability to talk about her experiences, and get a sense of herself as the sentient being at the center of those experiences. Even though she is born with certain complex and finely specialized talents, they would seem to equip her only lightly for the tasks ahead. Developmental psychologists have some of the biggest questions of all to grapple with: how a human being acquires both a private and a public self, whether language is a learnable skill or something reserved for those who have been biologically chosen, how the colors of consciousness can take root in a brain that starts out as raw, proliferating matter. Look closely enough at a developing mind, I would tell my students, and you can learn everything you need to know about being human.

Now these questions were coming alive for me in the most immediate way. With Athena’s arrival, the phenomenon that had so fascinated me from a distance had installed itself, delightfully, right in front of my eyes. Among all the other emotions of those heady days of new parenthood, I felt something like the surprise you feel when your new next-door neighbor turns out to be your boss, and you see your precious work-home balance disappearing along with your nude sun-bathing. Athena made demands on my professional responsibilities as well as my parental ones. She brought my work home with her. For the last three years I had observed this miracle in close-up, watching the momentous transformations of toddlerhood happen to my own precious firstborn. In those brief thousand days, our yowling neonate had turned into a person: social, moral, intelligent, articulate. I might not have been fully aware of when it happened, but somewhere along the line I had watched a consciousness emerge.

With each new milestone in Athena’s development, I mused about how the theories I had studied matched up with the realities I was witnessing. But I also found myself constantly wondering about the other, subjective side of the objective story. I wanted to understand what it was like to inhabit a mind that was a different thing every day, whose understanding of itself was changing so rapidly. I could find few insider testimonies to guide me through this period of life, either in the scientific writings I was familiar with, or in grown-up literature, where the experiences of the under-threes have hardly found a voice at all. For all the richness of their depictions of adult subjectivity, their willingness to eavesdrop on different forms of experience, novelists and poets have shown little interest in the unremembered atmospheres of toddlerhood. That neglect was startling, when all our scientific probings of the infant mind were showing that it was an interesting place to be.

Beyond the ordinary pleasures of fatherhood, my time at home with Athena promised to give me that insider’s view into a small child’s mind. With a little imaginative projection, I had the chance to put some subjective detail into the scientific background. Was there anything comparable to being a newborn baby, an infant on the threshold of language, a fiercely self-sufficient toddler? Would careful observation and questioning, enriched by the insights thrown up by new research, give me some clues as to how those experiences could be described? What do young children understand of their own consciousness, of their capacity to be there at the center of these colorful, chaotic experiences? How do you make sense of yourself, when that self has no continuity in time? These were some of the questions that had drawn me to the subject in the first place, and now fatherhood was giving me a chance to ask them all over again. The answers, if I got any, would not make me any better at parenting Athena, but they might make her a little less of a mystery.

The day after our visit to the Old Vienna Coffee House, I was going through some of the videos of Athena as a baby. I had been transferring our home movies to the computer, and we had been watching them in the mornings, when she crashed down the stairs in her pajamas, puffy-faced and euphoric from sleep. To the child who sat down with me to watch these video extracts, the baby on the screen did not even trigger the memory boost of self-recognition. I, too, could hardly recognize my daughter in the moon-faced two-month-old who now gazed out from my laptop. For the las...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPenguin Publishing Group

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 1583333975

- ISBN 13 9781583333976

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind by Fernyhough, Charles [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781583333976

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Paperback. Publisher overstock, may contain remainder mark on edge. Seller Inventory # 9781583333976B

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Softcover. Condition: New. Reprint. A father's intimate look at his daughter's developing mind from birth to age threeUnlike any other time in our lives, we remember almost nothing from our first three years. As infants, not only are we like the proverbial blank slate but our memories are like teflon: nothing sticks. In this beautifully written account of his daughter's first three years, Charles Fernyhough combines his vivid observations with a synthesis of developmental theory, re-creating what that time, lost to the memory of adults, is like from a child's perspective.In A Thousand Days of Wonder, Fernyhough, a psychologist and novelist, attempts to get inside his daughter's head as she acquires all the faculties that make us human, including social skills, language, morality, and a sense of self. Written with a father's tenderness and a novelist's empathy and style, this unique book taps into a parent's wonder at the processes of psychological development. Seller Inventory # DADAX1583333975

Thousand Days of Wonder : A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 9031327-n

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind 0.48. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9781583333976

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.53. Seller Inventory # 1583333975-2-1

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.53. Seller Inventory # 353-1583333975-new

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9781583333976

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1583333975

A Thousand Days of Wonder: A Scientist's Chronicle of His Daughter's Developing Mind

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1583333975