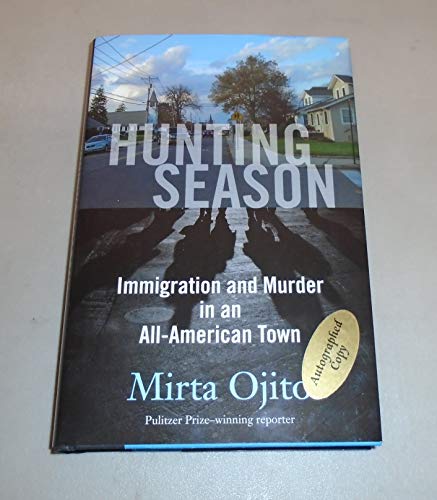

Items related to Hunting Season: Immigration and Murder in an All-American...

The true story of an immigrant's murder that turned a quaint village on the Long Island shore into ground zero in the war on immigration

In November 2008, Marcelo Lucero, a thirty-seven-year-old undocumented Ecuadorean immigrant, was attacked and murdered by a group of teenagers as he walked the streets of the Long Island village of Patchogue accompanied by a childhood friend. The attackers were out “hunting for beaners.” Chasing, harassing, and assaulting defenseless “beaners”—their slur for Latinos—was part of their weekly entertainment, some of the teenagers later confessed. Latinos—primarily men and not all of them immigrants—have become the target of hate crimes in recent years as the nation wrestles with swelling numbers of undocumented immigrants, the suburbs become the newcomers’ first destination, and public figures advance their careers by spewing anti-immigration rhetoric.

Lucero, an unassuming worker at a dry cleaner’s, became yet another victim of anti-immigration fever. In the wake of his death, Patchogue was catapulted into the national limelight as this formerly unremarkable suburb of New York became ground zero in the war on immigration. In death, Lucero became a symbol of everything that was wrong with our broken immigration system: fewer opportunities to obtain visas to travel to the United States, porous borders, a growing dependency on cheap labor, and the rise of bigotry.

Drawing on firsthand interviews and on-the-ground reporting, journalist Mirta Ojito has crafted an unflinching portrait of one community struggling to reconcile the hate and fear underlying the idyllic veneer of their all-American town. With a strong commitment to telling all sides of the story, Ojito unravels the engrossing narrative with objectivity and insight, providing an invaluable look at one of America’s most pressing issues.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Mirta Ojito, a newspaper reporter since 1987, has worked for the Miami Herald, El Nuevo Herald, and, from 1996 to 2002, the New York Times, where she covered immigration, among other beats, for the Metro desk. She has received numerous awards, including a shared Pulitzer Prize for national reporting in 2001 for a series in the Times about race in America. The author of Finding Mañana: A Memoir of a Cuban Exodus, she is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University in New York City.

On November 8, 2008, having had a few beers and an early dinner, Marcelo Lucero, an undocumented Ecuadorian immigrant, took a late-night stroll with his childhood friend Angel Loja near the train tracks in Patchogue, a seaside village of twelve thousand people in Suffolk County, New York, a county that only three years earlier had been touted by Forbes magazine as one of the safest and wealthiest in the United States. It is also one of the most segregated counties.

Before the mild moonlit night was over, Lucero was stabbed and killed by a gaggle of teenagers from neighboring towns, who had gone out hunting for “beaners,” the slur that, as some of them later told police, they used for Latinos. Earlier that night, they had harassed and beaten another Hispanic man—a naturalized US citizen from Colombia named Héctor Sierra. The teenagers also confessed to attacking Hispanics at least once a week.

Lucero was not the first immigrant killed by an enraged mob in the United States, and he most certainly will not be the last. At least two other immigrants were killed in the Northeast in 2008, but Lucero’s case is especially poignant because he was killed by a high school star athlete in an all-American town where people of mostly Italian and Irish descent proudly display US flags on the Fourth of July and every year attend a Christmas parade on Main Street. If it happened here, it can happen anywhere.

Patchogue, in central Long Island, is only about sixty miles from Manhattan—far enough to escape the city’s noise, dirt, and angst, but close enough to feel splashes of its excitement, pluck, and glamour. Lucero, who probably didn’t know about the Forbes ranking of the village as an idyllic place to live and raise children, had come from Ecuador to Patchogue in 1993 on the heels of others from his hometown who for thirty years now have been slowly and quietly making their way to this pocket of lush land named by the Indians who once inhabited it.

In Ecuador, too, Lucero had lived in a small village called Gualaceo. The town has lost so many of its people to Patchogue that those who remain call it Little Patchogue, a way to honor the dollars flowing there from Long Island. Month by month, remittances from New York have helped Gualaceños prosper despite a profound and long-lasting national economic crisis that forced the government to toss its national currency and adopt the US dollar more than a decade ago.

The day before he was killed, Lucero, thirty-seven, had been talking about going home. Over the years he had sent his family about $100,000—money earned working low-paying jobs—to buy land and build a three-story house he planned to share with his mother, his sister, and his nephew. He was eager to join them. The sister, Rosario, had asked him to be a father figure for her son. It’s time to go, Lucero told his younger brother, Joselo, who also lived in Patchogue.

“He was tired,” Joselo recalled. “He had done enough.”

Lucero was planning to leave before Christmas, an early present for their ailing mother. I’ll take you to the airport, Joselo promised. He never got the chance.

· · ·

I read about the murder of Marcelo Lucero when it was first reported in the news, but I learned some of the more intimate details through a Columbia University graduate student, Angel Canales, who had immediately jumped on the story and was working on a documentary about it for his master’s thesis. The story resonated with me for several reasons, not the least of them being my own condition as an immigrant. Though I never felt the burden of being in the country “illegally,” I have carried a different kind of stigma.

I came from Cuba in 1980, at sixteen, aboard a boat named Mañana, as part of a boatlift that brought more than one hundred twenty-five thousand Cuban refugees from the port of Mariel to the shores of South Florida in the span of five months. Several thousand of those refugees had committed crimes in Cuba and kept at it in their new country. Quickly, quicker than I could learn English or even understand what was happening around me, all of us were tainted by the unspeakable actions of a few. We became saddled with the label “Marielitos,” which carried a negative connotation, and with the narrative of Scarface, the unfortunate but popular film by Brian De Palma in which Al Pacino played a “Marielito” drug lord. It was a difficult stigma to shake. In 2005, when a book I wrote about the boatlift was published, people still felt the need to point to my story as a rarity—a successful “Marielita” who had done well and had even made it to the New York Times.

In fact, the opposite was true. My story was not unique. Most Mariel refugees were honest, decent, hard-working people. The exceptions had given us all a bad name. Those experiences taught me what it’s like to live under the shadow of an unpopular label, and while “illegal” is not as detrimental as “criminal,” it is close, and it has endured far longer than the “Marielito” curse.

The murder of Marcelo Lucero also resonated with me for a professional reason. It brought back memories of a story I had written for the New York Times on September 30, 1996, about a Hudson Valley village called Haverstraw, where, according to the 1990 census, 51 percent of the residents were Hispanic, although everyone knew the ratio was closer to 70 percent. Just thirty miles north of Manhattan, Haverstraw had been a magnet for Puerto Ricans since the 1940s. In more recent years, Dominicans had followed. The mayor, Francis “Bud” Wassmer, told me he no longer recognized the village where he had been born and raised. The public library carried an extensive selection of bilingual books, a local store that once sold men’s suits was selling work boots, the strains of merengue spilled from the pink windows of riverfront Victorian mansions, and the old candy store had closed down while eighteen bodegas had opened.

My story included the following paragraphs:

The suburbs, long the refuge of fleeing city dwellers, are quietly becoming a magnet to newly arrived immigrants, who, lured by relatives and the promise of a better life, are bypassing the city and driving to the proverbial American dream straight from the nation’s biggest international airports.

The trend, entrenched everywhere there is a significant immigrant population, is transforming the character of many suburbs, sociologists and demographers say. It is making suburbia more heterogeneous and interesting. But, like never before, it is also pressing onto unprepared suburban towns the travails and turmoil of the cities.

New immigrants, unlike immigrants who have lived in the country for a while, have special needs. They are likely not to speak English. They need jobs, help in finding affordable homes, guidance to enroll their children in schools, and information on how to establish credit and even open a checking account. They may also need public assistance to make ends meet until they find jobs. And they need it all in their own language.

Cities, where immigrants traditionally settled, have the services and the expertise to help new immigrants make a smoother transition to life in America. Places like the village of Haverstraw are not always fully equipped to deal with the needs of new immigrants.

“We have social problems just like urban communities,” Mr. [Ronaldo] Figueroa said, “but we don’t have the resources to address them in the same way, so they tend to accelerate at a greater pace than we can keep up with.”

Throughout the piece, I quoted the work of Richard D. Alba and John R. Logan, both sociology professors at the State University of New York at Albany, who had been researching how members of minority groups get along in suburbs of New York City, Chicago, Miami, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

“The question is how are they going to meet the needs of these new immigrants in a suburban environment?” Professor Logan told me. “This is very new for suburbia and it poses a challenge to public institutions.”

Twelve years later, when I heard about Lucero, I thought of Professors Logan and Alba, and I remembered the words of Mayor Wassmer, who told me that one of the problems he had with Hispanics in Haverstraw was that they produced a lot of garbage. Perplexed, I asked what he was referring to. He replied, “I mean, rice and beans are heavy, you know.” The other problem, as he saw it, was that Hispanics tended to walk in the streets and congregate at night by the tenuous light of the village’s old lampposts.

In fact, Lucero had been taking a stroll when he was attacked by seven teenagers and killed. Was it unusual in the village of Patchogue for people to walk late at night in its deserted streets? Was anyone there threatened by two Latino men out for a stroll? Was this the challenge that Logan had talked about, the turmoil that Figueroa had envisioned? The “problems” that the mayor had been able to discuss only by referring to garbage?

The Haverstraw story had always felt unfinished. As many reporters do, I had swooped in to collect information, filed a story, and moved on to the next assignment. I had never followed up. Patchogue, I thought, was my chance to connect the dots, to explore what could have happened—but, to my knowledge, never did—in Haverstraw.

That Lucero had been killed in a town so close to New York City and by youngsters who are only two or three generations removed from their own immigrant roots came as a shock even to those who for years have known that there was trouble brewing under the tranquil surface of suburbia.

“It’s like we heard the bells but we didn’t know if Mass was beginning or ending,” said Paul Pontieri Jr., the village’s mayor, who keeps in his office a photo of his Italian grandfather paving the roads of Patchogue. “I heard but I didn’t listen. I wish I had.”

But the killing did not surprise experts who track hate crimes and who knew that attacks against Hispanic immigrants had increased 40 percent between 2003 and 2007. According to the FBI, in 2008, crimes against Hispanics represented 64 percent of all ethnically motivated attacks.

In the two years that followed Lucero’s death, hate crime reports in Suffolk County increased 30 percent, a ratio closely aligned with national trends.8 It is unclear whether more attacks have taken place or if more victims, emboldened by the Lucero case, have come forward with their own tales of abuse.

Lucero’s murder, as well as the growing number of attacks against other immigrants, illustrates the angst that grips the country regarding immigration, raising delicate and serious questions that most people would prefer to ignore. What makes us Americans? What binds us together as a nation? How do we protect what we know, what we own? How can young men still in high school feel so protective of their turf and so angry toward newcomers that they can commit the ultimate act of violence, taking a life that, to them, was worthless because it was foreign?

Global movement—how to stimulate it and how to harness it—is the topic of this century. Few issues in the world today are as crucial and defining as how to deal with the seemingly endless flow of immigrants making their way to wealthier countries. Even the war against terrorism, which since 9/11 has become especially prominent, has been framed as an immigration challenge: who comes in, who stays out.

The relentless flow of immigrants impacts the languages we speak (consider the ongoing debate over bilingual education and the quiet acceptance in major cities, such as Miami and New York, of the predominance of Spanish), the foods we eat, the people we hire, the bosses we work for, and even the music we dance to. On a larger scale, immigrants affect foreign policy, the debate over homeland security, local and national politics, budget allocations, the job market, schools, and police work. No institution can ignore the role immigrants now play in shaping the daily life of most industrialized countries of the world.

In the United States immigration is at the heart of the nation’s narrative and sense of identity. Yet we continue to be conflicted by it: armed vigilantes patrol the Rio Grande while undocumented workers find jobs every day watching over our children or delivering food to our door. In 2011 members of Congress considered debating if the US-born children of undocumented immigrants ought to be rightful citizens of the country, while in Arizona Latino studies were declared illegal.

While the federal government spends millions of dollars building an ineffective wall at the US-Mexico border, the 11.1 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States wonder if the wall is being built to keep them out or in. In fact, 40 percent of undocumented immigrants, or more than four million people, did not climb a fence or dig a tunnel to get to the United States. They arrived at the nation’s airports as tourists, students, or authorized workers, and simply stayed once their visas expired.

The immigration debate affects not only Hispanic immigrants, who comprise the largest number of foreign-born people in the United States, but all immigrants. The Center for Immigration Studies, a Washington, DC, think tank, reported in August 2012 that the number of immigrants (both documented and undocumented) in the country hit a new record of forty million in 2010, a 28 percent increase over the total in 2000.

In a 2007 report researchers at the center generated population projections and examined the impact of different levels of immigration on the size and aging of American society. They found that if immigration continues at current levels, the nation’s population will increase to 468 million in 2060, a 56 percent increase from the current population. Immigrants and their descendants will account for 105 million, 63 percent of that increase. By 2060, one of every three people in the United States will be a Hispanic. Another study, released in 2011 by the Brookings Institution, revealed that “America’s population of white children, a majority now, will be in the minority during this decade.” Already minorities make up 46.5 percent of the population under eighteen.

As a nation we remain stumped over immigration. Are we still a nation of immigrants? Or are we welcoming only to those who follow the rules and, even more, look and act like us? In Suffolk County, the answers are complex.

The county likes people who have legal documents, who speak English, who don’t play volleyball in their backyards late into the night while drinking beer with buddies, who don’t produce a lot of garbage, who pay taxes, who know when and where t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBeacon Press

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 0807001813

- ISBN 13 9780807001813

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages264

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Hunting Season: Immigration and Murder in an All-American Town

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. Hardcover and dust jacket. Good binding and cover. Clean, unmarked pages. Seller Inventory # 2405230076

Hunting Season: Immigration and Murder in an All-American Town

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 252 pages. 9.25x5.75x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0807001813