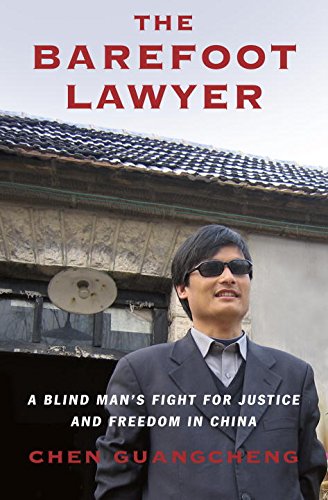

Items related to The Barefoot Lawyer: A Memoir

Chen Guangcheng is a unique figure on the world stage, but his story is even more remarkable than we knew. The son of a poor farmer in rural China, blinded by illness when he was an infant, Chen was fortunate to survive a difficult childhood. But despite his disability, he was determined to educate himself and fight for the rights of his country’s poor, especially a legion of women who had endured forced sterilizations under the hated “one child” policy. Repeatedly harassed, beaten, and imprisoned by Chinese authorities, Chen was ultimately placed under house arrest. After a year of fruitless protest and increasing danger, he evaded his captors and fled to freedom.

Both a riveting memoir and a revealing portrait of modern China, this passionate book tells the story of a man who has never accepted limits and always believed in the power of the human spirit to overcome any obstacle.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

CHAPTER ONE

A Child Apart

I cup my hands together, cradling a hard-boiled egg my mother has given me. It’s still warm. I am three or four years old and rarely given my own egg, so I hold off as long as I can before eating it. Wandering outside, I find the millstones where we grind our food, feeling for the top stone, carefully placing shell and rock together. I listen to the sounds of the village children laughing and playing in the yard, relatives and neighbors coming and going. I head back inside, climb onto a stool, and gently set the egg on the table. It begins to roll, but I can’t see it well enough to stop it. I hear the dull crack of shell against the dirt floor, then silence. If something bounces, rolls, makes a sound, I can use my ears to locate it, often with ease, but now I am at a loss. I strain my eyes, hoping to spot the egg, but all I can see are undifferentiated shapes. The neighbors and the children in the room don’t come to help me; instead they gawk at my trouble. Only my mother hurries over. She peels the egg, then folds it inside a jianbing crepe with some salted pickles and places it in my outstretched hands.

I was born in a remote Chinese village called Dongshigu on November 12, 1971, in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, a time of hardship and great bitterness. I was healthy at birth, but after five months a terrible fever set in, and we had no money for the hospital. Despite being acutely worried about my condition, my mother also had to feed and care for my four older brothers, aged five, eight, eleven, and fourteen. My father was working far away at the time, and we had no access to telephones; her in-laws, meanwhile, were consumed with their own affairs.

Making do on her own, my mother attended to every aspect of our lives. Each day she had to fetch water from a well near the Meng River, carrying buckets that swung on a pole over her shoulder. Before dawn she spent hours grinding food at our mill wheel to make the batter for the day’s jianbing. During the day, when she was not out working in the fields, she gathered wood and kindling for the cooking fire up in the hills. And always, she adhered to the strict work orders from the com- mune that organized how we worked, lived, and ate.

Her heart torn by my wild crying after I came down with the fever, my mother wrapped me in some old cloths and nestled me in a basket in the yard near where she worked. She would need two yuan to take me to a doctor at the local hospital, the only place with real medical care. But that was a substantial sum, for we had almost no money—my father earned only eighteen yuan a month at his job. In desperation, my mother set out to borrow the money from the head of her production team, who sent her to the bookkeeper, who sent her to the man respon- sible for financial matters. “How can you borrow money from us?” the man asked her incredulously. “You owe us money, and you haven’t earned enough grain points.” The communes were divided up into pro- duction brigades and even smaller production teams, and within the production team you earned points based on how much work you got done. You had to contribute at least as much as you ate, but with my mother the only adult working full-time, our family often fell behind. No points, no money, no doctor. The man told my mother to get a let- ter from the head of the production team, but she knew he was just trying to get rid of her.

Discouraged and distraught, she went to friends and relatives and tried to borrow money, but there was none to be had. The village “bare- foot doctor,” a farmer who had received very basic medical training to provide care in remote rural areas, had no idea how to bring down my fever.

I cried for two whole days and two whole nights, my tiny body burning and squirming in my mother’s arms. On the third day, my mother was up at her usual early hour, preparing food for the family, when she heard my terrible wailing begin again. She picked me up to breast-feed me but recoiled in terror when she saw the blue masses clouding my dark eyes. She rushed me to an old woman in a nearby village who had some experience with home remedies. Her cure, after examining me, was to blow on my eyes; of course, there was no change in my condition.

My parents never knew the nature of my illness or why my fever caused me to go blind. After returning home a month later and learning what had happened, my father arranged to take me to the local clinic. By then it was too late for my eyes, but my father was determined to find a cure, and over the next several years my parents took me to doctor after doctor, each time in vain. One said it was keratitis, another said glaucoma, but they all concluded that there was nothing they could do.

Whatever the cause of my fever, the results were unforgiving. In my earliest memories I see only splashes of color, and only if an object is right in front of my eyes. Sometimes I like to say that I was blinded by communism—or, more specifically, a wave of unrealistic, empty propaganda that swept the country continually for decades. The Com- munist Party, the bringer of “scientific development,” liked to boast about its hospitals and its free health care, about how well people were treated and how much better things were now than in the past. But the truth is that we lacked the most basic medical care and were always at the mercy of illness. Death came for us often. Two years before I was born, in fact, my mother had given birth to a baby girl, the daughter she’d been longing for after bearing four sons. When the baby sick- ened, she had no money for the hospital, and finally there was little my mother could do but wait and hope. My sister had what the villagers called “the seven-day sickness,” and, indeed, she was dead after eight or nine days. If the girl had survived, my mother later told me, I would probably never have been born.

Now four years old, I am hanging suspended between heaven and earth. As my brother pulls from above, I rise in the air. Three, five, ten feet up—no fear, only joy. Higher up in the persimmon tree, I can hear everything, every sound etched in the air. I hear the reverberating calls of birds, their overlapping, melodic lines spinning through the trees, and the sounds at a spring nearby, where the villagers are using ladles to scoop up water, the liquid splashing into the buckets and jugs; I can distinguish the minute changes in pitch, from the first plashing into an empty bucket to that quickening sound when it’s almost full. All around I hear a chorus of life: songbirds trilling, animals lowing, bleating, barking, each one with its particular intensity, its own pattern of rising and falling, each moving in and out of rhythm with the others.

We have done this before, Third Brother and I. He loves to climb trees and catch birds, and this is how he takes me with him. He secures one end of a rope around my waist; holding the other end, he climbs up the tree and ties the rope tight at the fork of two sturdy branches. I stand beneath the tree, waiting. He strains to pull me up, little by little, until I reach that fork in the tree, where I can sit in perfect contentment. At first I simply hold the branch, but soon I grow bold, touching everything around me.

Above me are persimmons, branches lined with them. I ask my brother to pick one for me. “You know you can’t eat them,” he says. “They’re not ripe yet, and you can die from eating an unripe persimmon.” “I know,” I reply. He climbs up to a higher branch to pick out the biggest and roundest one he can find. My hands are so small that I can barely hold the persimmon in one hand while still hugging the tree with the other. My enchantment is complete—I stare at the brightness of the fruit’s reds and yellows, feeling in my palm its smooth and finely textured skin. I hold the persimmon close to my face, almost touching my lips. The feel and smell are so enticing that I can no longer help myself: I take a small, secret bite off the pointed tip. At first the taste is sweet, but when I take a second, larger bite, my lips pucker, and I remember my brother’s warning. I spit out the second bite quickly.

Seeing that something is wrong, Third Brother climbs down to me and asks, “Did you eat it?” I am afraid he will be angry with me, so I hold the part I’d bitten inside my palm, out of sight. In a small voice I lie, saying I hadn’t. “Let me see your persimmon,” he says, prying open my hand and finding it. “Why did you eat it?” he asks. I had promised not to, so I don’t know what to say.

“How do persimmons grow on branches?” I ask my brother a few minutes later, when he is once again scampering up above me. He bends a branch laden

with fruit toward me, close enough to touch. With one hand I hold the fruit I’ve already bitten; with the other I feel my way across the slippery bark, finding two glossy persimmons that are growing together. I grab one of them and twist it, but my brother warns me not to pick it and tells me to let go. As soon as I do, the branch snaps back into place, the persimmons trembling.

Someone approaches from along the road, footsteps shuffling rhythmically on the packed dirt. “How on earth did that child get so high up in that tree?” a woman calls out. “Don’t you know that’s dangerous?” Third Brother replies, “It’s okay. We’ve done this many times before at home.”

When I’ve finally had enough, I shout, “Let’s go down!” My brother slowly uncoils the rope, length by length. I reach out to touch the tree bark one more time. When I am close to the ground, I start swinging and spinning back and forth. I am not afraid—I am thrilled. I feel nothing but freedom, all the way down.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAllen Lane

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 0670067679

- ISBN 13 9780670067671

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Barefoot Lawyer: A Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks99253