Items related to A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past...

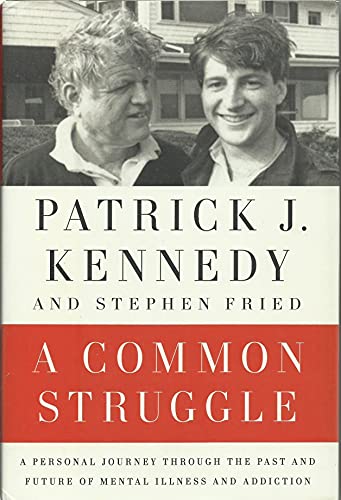

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction - Hardcover

In this New York Times bestseller Patrick J. Kennedy, the former congressman and youngest child of Senator Ted Kennedy, details his personal and political battle with mental illness and addiction, exploring mental health care's history in the country alongside his and every family's private struggles.

On May 5, 2006, the New York Times ran two stories, “Patrick Kennedy Crashes Car into Capitol Barrier” and then, several hours later, “Patrick Kennedy Says He'll Seek Help for Addiction.” It was the first time that the popular Rhode Island congressman had publicly disclosed his addiction to prescription painkillers, the true extent of his struggle with bipolar disorder and his plan to immediately seek treatment. That could have been the end of his career, but instead it was the beginning.

Since then, Kennedy has become the nation’s leading advocate for mental health and substance abuse care, research and policy both in and out of Congress. And ever since passing the landmark Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act—and after the death of his father, leaving Congress—he has been changing the dialogue that surrounds all brain diseases.

A Common Struggle weaves together Kennedy's private and professional narratives, echoing Kennedy's philosophy that for him, the personal is political and the political personal. Focusing on the years from his 'coming out' about suffering from bipolar disorder and addiction to the present day, the book examines Kennedy's journey toward recovery and reflects on Americans' propensity to treat mental illnesses as "family secrets."

Beyond his own story, though, Kennedy creates a roadmap for equality in the mental health community, and outlines a bold plan for the future of mental health policy. Written with award-winning healthcare journalist and best-selling author Stephen Fried, A Common Struggle is both a cry for empathy and a call to action.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

www.patrickjkennedy.net

Stephen Fried is an award-winning magazine journalist, a best-selling author and an adjunct professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is the author of two books on healthcare, mental health and addiction--Bitter Pills: Inside the Hazardous World of Legal Drugs and Thing of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia—as well as The New Rabbi, Husbandry and his recent historical biography Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West—One Meal at a Time, which was a New York Times bestseller. Fried lives in Philadelphia with his wife, author Diane Ayres.

www.stephenfried.com

PROLOGUE

I’m never going to remember what actually happened that night in early May of 2006 when I slammed my green Mustang into the police barrier in front of the US Capitol. I retain a faint memory of flashing lights and people in uniforms knocking at my car window. That’s about it. No idea how I got there. No idea how I got home.

But I will never forget what happened the next day. I got up late, walked from my apartment building to Capitol Hill (because I had no idea where my car was), and then sat in my congressional office waiting in terror for the phone to ring.

I was waiting for someone to call and say: “You finally did it, you killed somebody. This is it.”

When the call didn’t come, I drank a couple Red Bulls to try to clear my head and took a meeting with the leaders of the Campaign for Mental Health Reform, which was lobbying on behalf of patient, provider, and clinician groups. They immediately noticed I didn’t appear mentally healthy myself: I was having trouble following the conversation and my hands were shaking. We were all saved from further embarrassment when I was called away to the House floor to vote on a lot of amendments for a port safety bill.

As the voting ended, the phone call finally came. I was summoned off the House floor into the cloakroom, where there were booths that allowed private conversations. It was my chief of staff.

“Patrick,” he said, “we have a problem.”

Apparently I had half woken up at around two thirty in the morning, several hours after mixing medications to get to sleep—Ambien and Phenergan, both recently prescribed, along with all the other asthma and mental health meds I was taking. Convinced I was late for a vote, I threw on a suit and tie, stumbled to my car, and drove, headlights off, several blocks down Third Street until I barely managed the left onto C Street. Then I barreled straight toward the security station for the House of Representatives. I swerved into oncoming traffic, nearly hitting a US Capitol Police vehicle, which somehow dodged me and then made a quick U-turn to chase me. I slowed down but didn’t stop until my car slammed into the security barrier.

Luckily, my chief of staff explained, only my car was damaged, because nobody was on the streets or the sidewalks where I was driving in the middle of the night.

After making sure I wasn’t hurt, the Capitol Police quietly took me home and moved my car into the congressional parking lot. But word spread and someone from the media had noticed the banged-up car in the lot.

“You’ve got to get back here, right now,” my chief of staff said.

I made a beeline back to my office and barricaded myself in. The next hours were a blur of phone calls of support and tough questions for which there were no easy answers. But the call I remember best came from my dad.

The first thing he said was, “I saw a picture of the car, and I don’t know why they’re making such a big deal of this. It looked to me like it was only a little fendah bendah.”

Very old-school. No “How are you doing?” Just “a little fendah bendah” (or, for those not raised in New England, “fender bender”).

In fact, that’s pretty much how he suggested I play it with the press and the public.

I wanted him to understand that I was sick, and that untreated mental illness and addiction was not about little fendah bendahs. It was about multicar pileups where people were injured and killed.

His insistence that this was a fendah bendah was a key to our issues as father and son. I worshipped my dad. He was the North Star by which I navigated my life. My dad loved and supported me as best he could, but he didn’t always respect me, and he didn’t understand the chronic medical condition I struggled with. He often said that all I needed was a “good swift kick in the ass.”

Did I say any of this to him? Of course not. I grew up among people who were geniuses at not talking about things. When I was a teenager going for therapy during my parents’ divorce, I wouldn’t tell my psychiatrist the truth because I wasn’t sure I could trust him to keep things private. Then one day I walked into a bookstore and browsed the “Kennedy section” and saw that many of the books included the “family secrets” I had refused to discuss. But I still wouldn’t talk about them.

So my father was stunned when, several hours later, I admitted everything that happened to the press and then very publicly left for an extended rehab at the Mayo Clinic. He was also pretty concerned when I tried to demand jail time in my plea agreement so it wouldn’t look like I was getting preferential treatment.

And my dad was really not thrilled when, after returning from rehab, I started being much more public about my private struggles with bipolar disorder and addiction. I promised myself I would have the most transparent recovery and treatment ever, all but donating my brain and its diseases to science while I was still living. I wanted to aggressively tie my personal story to my ongoing legislative fight for mental health parity—an effort to outlaw the rampant discrimination in medical insurance coverage for mental illness and addiction treatment. And winning the parity fight would be the first step to overcoming all discrimination against people with these diseases, their families, and those who treated them.

So I decided to go public exclusively to the New York Times. I did this with my Republican House colleague Jim Ramstad from Minnesota. Before my crash I had known him, although not well, as one of the only members of Congress who was openly in recovery. But after my arrest and hospitalization he was the first one to come visit me at the Mayo Clinic. I asked if he would be my sponsor in recovery—I had never had a real sponsor before—and he invited me into his network of friends in recovery on Capitol Hill.

While we thought this could have an impact, there was no way we could have predicted that the resulting story would run huge on the front page of the Times—or that it would run on September 19, 2006, two days after the death of my father’s sister Patricia Kennedy Lawford and the day before her funeral in New York City. There was also no way to predict that the reporter would quote me talking about the veil of secrecy in my family regarding depression and substance use, and then call my dad for comment about his own drinking habits at such a sensitive time.

So, of course, he was livid. When the family gathered after the funeral service at my Aunt Pat’s house in New York, he cornered me. He called the article a “disaster”—the word he always used to describe the most extreme situations. How dare I talk about the family this way? How dare I discuss “these things” in public?

I stood there on the verge of disintegration. I was early in my sobriety and still pretty vulnerable. And I watched my father circulate around the room, talking about the article.

Then my cousin Anthony Shriver came up to tell me what his sister, Maria, had just done. When my dad got to her to complain about the Times story, she apparently challenged him.

“I think what Patrick did was fantastic,” Maria said. “That’s what we need in our family, someone to talk about this.”

And, in that moment, I knew what I had to do.

—

THIS ISSUE OF not talking openly about “these things” is hardly just a Kennedy issue. It is a problem in most American families. Most of the challenges of mental illness and addiction feel incredibly unique and private when, in fact, they are remarkably common: nearly 25 percent of all Americans are personally affected by mental illness and addiction every day, one-third of all U.S. hospital stays involve these diseases, and they have a huge impact on everyone else.

But, in this situation, there was a very specific, very personal and political way for me to address this on Capitol Hill. It was a bill called the Mental Health Parity Act.

Ten years earlier, a mental health equity act had been signed into law. It was supposed to finally end prejudice against mental illness by making it illegal to treat diseases of the brain any differently than those of any other part of the body.

The act had failed. And now it was up for renewal. I was lead Democratic sponsor of the House version, my father was lead Democratic sponsor of the Senate version, and the two bills couldn’t have been more different.

The Senate bill was much the same one that had failed to make much impact ten years ago—in part because, as a matter of political expediency, it only covered what are called the most “serious” mental illnesses (such as schizophrenia) and ignored more common mental illnesses and substance use disorders.

My bill included all the brain diseases. House Resolution (HR) 1424 was meant to be a kind of medical civil rights act, which once and for all would end—or at least make illegal—any discrimination in coverage for these illnesses.

Basically, in my dad’s Senate bill, what was wrong with me—bipolar disorder, addiction—would not be fully covered, would not be medically equal. In my bill, they would be.

But, of course, it was all much more complicated than that.

—

ALMOST SIX YEARS after that front-page New York Times story about my recovery, I slipped very quietly into the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

Again.

I ended up in the Generose Building. That’s where they do psychiatric care, and drug and alcohol rehab. After checking in at the front desk, I was brought to see the same doctors who had treated me there before, along with my favorite counselor, John Holland. He runs the infamous “process groups,” which are like AA meetings on steroids—very intense—with your peers just smashing down your denial.

John and I caught up. Since the last time we had seen each other, a lot had happened. My father had died, I had left Congress, I had fallen in love, I had truly committed to sobriety, I had gotten married for the first time at age forty-four, and I had moved from New England to the Jersey Shore, where my wife, Amy, and her family lived. We had just had a son and were also raising her daughter from a previous marriage.

I also shared with him a recent devastating loss: my older sister, Kara. John knew Kara but hadn’t known about her sudden, unexpected death at fifty-one.

He said that he had recently lost his older sister. Drug overdose.

It was a relief to be able to tell him that I wasn’t there to be admitted. I was there to see a friend and colleague who had been texting me from rehab, asking for my help.

I was led through several doors, each one locked behind us, into the corridors of the Generose Building, where I had walked so many times before. I was finally brought to a patient room where the door was opened to reveal my longtime fellow Congressman Jesse Jackson Jr., sitting on the edge of a hospital bed.

I was stunned by how dejected he was—what a grip depression had on him. I had served with Jesse for sixteen years and saw him all the time because we were on a lot of the same subcommittees together. And he always had this kind of bravado about him—a proud guy with an incredible physical bearing and this power personality. Now he was really frightened by the depth of his own despair.

He said he had put on his nice shirt because I was coming. He was now measuring things differently in life—the simplest act, of putting on a clean dress shirt, had become a big gesture. It was hard.

Jesse had been secretly suffering from bipolar disorder. Although his family was insisting he was being treated for, you know, “exhaustion,” he realized it was time to come clean. But he wasn’t in any condition to do that yet. Nobody close to him really understood. So he wanted me to be the messenger.

I sat down next to him and we talked. He spoke achingly about his kids and what kind of father he was, how he felt he had let everybody down. He said he couldn’t imagine not being there to walk his daughter down the aisle. When I thought about what that meant—that he wasn’t sure he would live through this—it left me speechless.

I figured the best way to encourage him was to tell him about how it was when I was in his situation. He knew I had been treated at Generose in May 2006 after the car crash. But what he didn’t know, because nobody did, was that part of the reason I wrecked my life was because I failed to take my treatment seriously enough when I was at Mayo five months before the crash, during Congress’s Christmas break in 2005.

During that previous hospitalization, I tried to game the situation, refusing to be treated in Generose because of the stigma. I didn’t want anyone to think I was “crazy.” So I forced them to keep me at the medical facility at Mayo, where I could detox from opiates but still, technically, not be in rehab. I got treated physically but not mentally and spiritually. And after that treatment, I only stopped using opiates—not the other drugs I used, which didn’t have such a pejorative label. When you’re good at self-medicating, you can abuse just about anything.

I told Jesse I was glad he wasn’t making the same mistake and was committed to doing the treatment right. Everyone finding out wasn’t such a bad thing. In fact, everyone finding out was probably the only reason I was still here. But, at the time, I hadn’t known what was going to happen; I felt my life was over and I had let everyone down. I was a loser and a failure.

“I know, I know,” he said, nodding his head. “But I don’t know who I’m supposed to be anymore. My father is this great man and I’ve been trying to be a great man, but I don’t know if I can be.”

I told him he was a great man and this was going to make him an even greater man. And, frankly, in the political world we live in, his openness on mental health would advance the cause of civil rights as much as anything he had ever done. Because it’s all about overcoming stereotypes, prejudice, and marginalization.

He asked if I’d be willing to tell his father that. As quickly as I said yes, he was speed-dialing the number on his cell phone. I thought it was funny when he handed it to me and said, “Here’s the reverend.”

I explained what Jesse Jr. and I had been discussing, and he declared, as if he were in the middle of a sermon, “The cross is a lot easier to bear if you’re not bearing it alone.” I actually had to stop myself from saying “Amen.”

I told the reverend that I wasn’t sure which was a heavier cross to bear, being Ted Kennedy’s son or being his son—at which point Jesse, sitting next to me, started to smile for the first time, and actually laughed.

After we wrapped up the call, Jesse was talking about the sense of persecution he felt, and his confusion about whether to resign from Congress—because of the ethics investigation he was in the middle of and because of his illness. It turned out he was in the same healthcare dilemma as so many other Americans.

“I can’t resign,” he said. “I need to finish my treatment, and I won’t get any care if I resign. All these years I never needed healthcare. Now when I need it, how am I going to get it?” This was also making him wonder how his constituents got menta...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBlue Rider Press

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 0399173323

- ISBN 13 9780399173325

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number4

- Number of pages432

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0399173323-2-1

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0399173323-new

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. New. Seller Inventory # 27-06741

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0399173323

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0399173323

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0399173323

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 422 pages. 9.50x6.50x1.25 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0399173323

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0399173323

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0399173323

A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0399173323