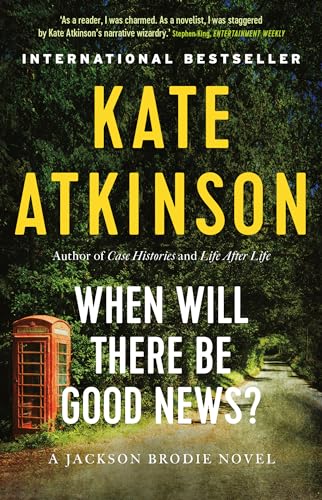

Items related to When Will There Be Good News?

International Bestseller

When Will There Be Good News? is the brilliant new novel from the acclaimed author of Case Histories and One Good Turn, once again featuring private investigator Jackson Brodie.

Thirty years ago, six-year-old Joanna witnessed the brutal murders of her mother, brother and sister, before escaping into a field, and running for her life. Now, the man convicted of the crime is being released from prison, meaning Dr. Joanna Hunter has one more reason to dwell on the pain of that day, especially with her own infant son to protect.

Sixteen-year-old Reggie, recently orphaned and wise beyond her years, works as a nanny for Joanna Hunter, but has no idea of the woman’s horrific past. All Reggie knows is that Dr. Hunter cares more about her baby than life itself, and that the two of them make up just the sort of family Reggie wished she had: that unbreakable bond, that safe port in the storm. When Dr. Hunter goes missing, Reggie seems to be the only person who is worried, despite the decidedly shifty business interests of Joanna’s husband, Neil, and the unknown whereabouts of the newly freed murderer, Andrew Decker.

Across town, Detective Chief Inspector Louise Monroe is looking for a missing person of her own, murderer David Needler, whose family lives in terror that he will return to finish the job he started. So it’s not surprising that she listens to Reggie’s outrageous thoughts on Dr. Hunter’s disappearance with only mild attention. But when ex-police officer and Private Investigator, Jackson Brodie arrives on the scene, with connections to Reggie and Joanna Hunter of his own, the details begin to snap into place. And, as Louise knows, once Jackson is involved there’s no telling how many criminal threads he will be able to pull together — or how many could potentially end up wrapped around his own neck.

In an extraordinary virtuoso display, Kate Atkinson has produced one of the most engrossing, masterful, and piercingly insightful novels of this or any year. It is also as hilarious as it is heartbreaking, as Atkinson weaves in and out of the lives of her eccentric, grief-plagued, and often all-too-human cast. Yet out of the excesses of her characters and extreme events that shake their worlds comes a relatively simple message, about being good, loyal, and true. When Will There Be Good News? shows us what it means to survive the past and the present, and to have the strength to just keep on keeping on.

From the Hardcover edition.

When Will There Be Good News? is the brilliant new novel from the acclaimed author of Case Histories and One Good Turn, once again featuring private investigator Jackson Brodie.

Thirty years ago, six-year-old Joanna witnessed the brutal murders of her mother, brother and sister, before escaping into a field, and running for her life. Now, the man convicted of the crime is being released from prison, meaning Dr. Joanna Hunter has one more reason to dwell on the pain of that day, especially with her own infant son to protect.

Sixteen-year-old Reggie, recently orphaned and wise beyond her years, works as a nanny for Joanna Hunter, but has no idea of the woman’s horrific past. All Reggie knows is that Dr. Hunter cares more about her baby than life itself, and that the two of them make up just the sort of family Reggie wished she had: that unbreakable bond, that safe port in the storm. When Dr. Hunter goes missing, Reggie seems to be the only person who is worried, despite the decidedly shifty business interests of Joanna’s husband, Neil, and the unknown whereabouts of the newly freed murderer, Andrew Decker.

Across town, Detective Chief Inspector Louise Monroe is looking for a missing person of her own, murderer David Needler, whose family lives in terror that he will return to finish the job he started. So it’s not surprising that she listens to Reggie’s outrageous thoughts on Dr. Hunter’s disappearance with only mild attention. But when ex-police officer and Private Investigator, Jackson Brodie arrives on the scene, with connections to Reggie and Joanna Hunter of his own, the details begin to snap into place. And, as Louise knows, once Jackson is involved there’s no telling how many criminal threads he will be able to pull together — or how many could potentially end up wrapped around his own neck.

In an extraordinary virtuoso display, Kate Atkinson has produced one of the most engrossing, masterful, and piercingly insightful novels of this or any year. It is also as hilarious as it is heartbreaking, as Atkinson weaves in and out of the lives of her eccentric, grief-plagued, and often all-too-human cast. Yet out of the excesses of her characters and extreme events that shake their worlds comes a relatively simple message, about being good, loyal, and true. When Will There Be Good News? shows us what it means to survive the past and the present, and to have the strength to just keep on keeping on.

From the Hardcover edition.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Kate Atkinson was born in York in 1951, where her parents ran a surgical supplies shop, and spent a lot of time reading as a child. She’s even commented that being an only child and learning to enjoy her own company, combined with her love of books, probably helped prepare her well for the solitary life of the writer. Atkinson then attended the University of Dundee, where she studied literature and completed a doctoral thesis on the history of the short story form, and came close to pursuing an academic career. However, it was when she left the university and began writing fiction as an escape from the day-to-day domesticity of child-raising and home-making that the seeds of Atkinson’s true calling appeared — the first story she ever sent off for consideration won a major prize, the Woman’s Own Short Story Competition. As she’s explained in one interview, “That was how I became a writer, really. It was a very slow burn. That was from first putting pen to paper around 1982 to winning that competition in 1986 to a novel being accepted in 1994.” That first novel, Behind the Scenes at the Museum, went on to win the prestigious Whitbread Prize for Book of the Year in 1995.

Ever since, Kate Atkinson has been an internationally bestselling author. Her next novels, Human Croquet (1997) and Emotionally Weird (2000), were followed by a collection of short stories called Not the End of the World (2002). It was with this book that Atkinson began to experiment with other narrative points of view. As she explained in one interview, “I had really had enough of the first person by the time I had done with the third book... It was one of the many reasons I wrote a collection of stories at that point, because I wanted to break that voice and get away from it, as well as explore other voices. With stories you can get away with more, and move around, try things on... Once I got the hang of it I found it very liberating, because once you know that character and you want to write them, you just step into their head and think like they think and you write it down, so you can be very fluid and direct.”

Next came Case Histories (2004), a novel that marked Atkinson’s first foray into crime fiction — a label that Atkinson finds to be quite limiting, considering that all of her books have involved mystery or crime elements, and genre classification can be so narrow-minded and elitist. As she explained in one interview, “There are good books, bad books, mediocre books. Why is it necessary to say it’s not any good because it is a crime novel, a romance, or whatever? Jane Austen wrote romance for heaven’s sake. Dickens wrote crime novels.” At the same time, though, Atkinson is a fan of crime fiction herself, so the label doesn’t really bother her — just those people who use it pejoratively. Anyway, the critics and award panels have agreed with Atkinson: Case Histories won the Saltire Book of the Year Award and the Prix Westminster, and has received worldwide acclaim. As the Guardian reviewer put it, the novel was her “best book yet, an astonishingly complex and moving literary detective story that made me sob but also snort with laughter. It’s the sort of novel you have to start rereading the minute you've finished it.”

Case Histories also marks the first appearance of private detective Jackson Brodie (who has proven to be immensely popular with readers), as he attempts to unravel the truth behind three crime files that have been left stagnant for years. And it is in this story — or rather the multiple storylines that make it up — that Atkinson truly begins to play with using different perspectives to gradually unveil her plot. The New York Times described her style as having a “cinematic cleverness,” where characters are left out when you’d expect them to be present, or the point of view changes abruptly, or small “hiccups in time” can add new layers of meaning. Atkinson would bring back both Jackson Brodie and this narrative style with her novel One Good Turn (2006), which is set during the Edinburgh Festival and once again places Brodie at the heart of multiple intersecting mysteries. “The most fun I’ve had with a novel this year,” Ian Rankin noted.

Atkinson’s latest novel, When Will There be Good News?, is the third to feature Jackson Brodie, although the author says she “never thought of it as a trilogy”: “I just thought of it as three books with the same character moving on and evolving, I think, so that by the end of book three, Jackson is in a very different place to what he was at the beginning of book one.” And while Atkinson is herself moving on with her next project — an unrelated novel featuring two female characters at a murder mystery weekend — she does hope to return to Jackson Brodie one day. But for now she feels that the end of When Will There Be Good News? is a “good place to leave him, because he needs to recover, I think, from all kinds of things that have happened to him.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Ever since, Kate Atkinson has been an internationally bestselling author. Her next novels, Human Croquet (1997) and Emotionally Weird (2000), were followed by a collection of short stories called Not the End of the World (2002). It was with this book that Atkinson began to experiment with other narrative points of view. As she explained in one interview, “I had really had enough of the first person by the time I had done with the third book... It was one of the many reasons I wrote a collection of stories at that point, because I wanted to break that voice and get away from it, as well as explore other voices. With stories you can get away with more, and move around, try things on... Once I got the hang of it I found it very liberating, because once you know that character and you want to write them, you just step into their head and think like they think and you write it down, so you can be very fluid and direct.”

Next came Case Histories (2004), a novel that marked Atkinson’s first foray into crime fiction — a label that Atkinson finds to be quite limiting, considering that all of her books have involved mystery or crime elements, and genre classification can be so narrow-minded and elitist. As she explained in one interview, “There are good books, bad books, mediocre books. Why is it necessary to say it’s not any good because it is a crime novel, a romance, or whatever? Jane Austen wrote romance for heaven’s sake. Dickens wrote crime novels.” At the same time, though, Atkinson is a fan of crime fiction herself, so the label doesn’t really bother her — just those people who use it pejoratively. Anyway, the critics and award panels have agreed with Atkinson: Case Histories won the Saltire Book of the Year Award and the Prix Westminster, and has received worldwide acclaim. As the Guardian reviewer put it, the novel was her “best book yet, an astonishingly complex and moving literary detective story that made me sob but also snort with laughter. It’s the sort of novel you have to start rereading the minute you've finished it.”

Case Histories also marks the first appearance of private detective Jackson Brodie (who has proven to be immensely popular with readers), as he attempts to unravel the truth behind three crime files that have been left stagnant for years. And it is in this story — or rather the multiple storylines that make it up — that Atkinson truly begins to play with using different perspectives to gradually unveil her plot. The New York Times described her style as having a “cinematic cleverness,” where characters are left out when you’d expect them to be present, or the point of view changes abruptly, or small “hiccups in time” can add new layers of meaning. Atkinson would bring back both Jackson Brodie and this narrative style with her novel One Good Turn (2006), which is set during the Edinburgh Festival and once again places Brodie at the heart of multiple intersecting mysteries. “The most fun I’ve had with a novel this year,” Ian Rankin noted.

Atkinson’s latest novel, When Will There be Good News?, is the third to feature Jackson Brodie, although the author says she “never thought of it as a trilogy”: “I just thought of it as three books with the same character moving on and evolving, I think, so that by the end of book three, Jackson is in a very different place to what he was at the beginning of book one.” And while Atkinson is herself moving on with her next project — an unrelated novel featuring two female characters at a murder mystery weekend — she does hope to return to Jackson Brodie one day. But for now she feels that the end of When Will There Be Good News? is a “good place to leave him, because he needs to recover, I think, from all kinds of things that have happened to him.”

From the Hardcover edition.

I

In the Past

Harvest

The heat rising up from the tarmac seemed to get trapped between the thick hedges that towered above their heads like battlements.

‘Oppressive,’ their mother said. They felt trapped too. ‘Like the maze at Hampton Court,’ their mother said. ‘Remember?’

‘Yes,’ Jessica said.

‘No,’ Joanna said.

‘You were just a baby,’ their mother said to Joanna. ‘Like Joseph is now.’ Jessica was eight, Joanna was six.

The little road (they always called it ‘the lane’) snaked one way and then another, so that you couldn’t see anything ahead of you. They had to keep the dog on the lead and stay close to the hedges in case a car ‘came out of nowhere’. Jessica was the eldest so she was the one who always got to hold the dog’s lead. She spent a lot of her time training the dog, ‘Heel!’ and ‘Sit!’ and ‘Come!’ Their mother said she wished Jessica was as obedient as the dog. Jessica was always the one who was in charge. Their mother said to Joanna, ‘It’s all right to have a mind of your own, you know. You should stick up for yourself, think for yourself,’ but Joanna didn’t want to think for herself.

The bus dropped them on the big road and then carried on to somewhere else. It was ‘a palaver’ getting them all off the bus. Their mother held Joseph under one arm like a parcel and with her other hand she struggled to open out his newfangled buggy. Jessica and Joanna shared the job of lifting the shopping off the bus. The dog saw to himself. ‘No one ever helps,’ their mother said. ‘Have you noticed that?’ They had.

‘Your father’s country fucking idyll,’ their mother said as the bus drove away in a blue haze of fumes and heat. ‘Don’t you swear,’ she added automatically, ‘I’m the only person allowed to swear.’

They didn’t have a car any more. Their father (‘the bastard’) had driven away in it. Their father wrote books, ‘novels’. He had taken one down from a shelf and shown it to Joanna, pointed out his photograph on the back cover and said, ‘That’s me,’ but she wasn’t allowed to read it, even though she was already a good reader. (‘Not yet, one day. I write for grown-ups, I’m afraid,’ he laughed. ‘There’s stuff in there, well . . .’)

Their father was called Howard Mason and their mother’s name was Gabrielle. Sometimes people got excited and smiled at their father and said, ‘Are you the Howard Mason?’ (Or sometimes, not smiling, ‘that Howard Mason’ which was different although Joanna wasn’t sure how.)

Their mother said that their father had uprooted them and planted them ‘in the middle of nowhere’. ‘Or Devon, as it’s commonly known,’ their father said. He said he needed ‘space to write’ and it would be good for all of them to be ‘in touch with nature’. ‘No television!’ he said as if that was something they would enjoy.

Joanna still missed her school and her friends and Wonder Woman and a house on a street that you could walk along to a shop where you could buy the Beano and a liquorice stick and choose from three different kinds of apples instead of having to walk along a lane and a road and take two buses and then do the same thing all over again in reverse.

The first thing their father did when they moved to Devon was to buy six red hens and a hive full of bees. He spent all autumn digging over the garden at the front of the house so it would be ‘ready for spring’. When it rained the garden turned to mud and the mud was trailed everywhere in the house, they even found it on their bed sheets. When winter came a fox ate the hens without them ever having laid an egg and the bees all froze to death which was unheard of, according to their father, who said he was going to put all those things in the book (‘the novel’) he was writing. ‘So that’s all right then,’ their mother said.

Their father wrote at the kitchen table because it was the only room in the house that was even the slightest bit warm, thanks to the huge temperamental Aga that their mother said was ‘going to be

the death of her’. ‘I should be so lucky,’ their father muttered. (His book wasn’t going well.) They were all under his feet, even their mother.

‘You smell of soot,’ their father said to their mother. ‘And cabbage and milk.’

‘And you smell of failure,’ their mother said.

Their mother used to smell of all kinds of interesting things, paint and turpentine and tobacco and the Je Reviens perfume that their father had been buying for her since she was seventeen years old and ‘a Catholic schoolgirl’, and which meant ‘I will return’ and was a message to her. Their mother was ‘a beauty’ according to their father but their mother said she was ‘a painter’, although she hadn’t painted anything since they moved to Devon. ‘No room for two creative talents in a marriage,’ she said in that way she had, raising her eyebrows while inhaling smoke from the little brown cigarillos she smoked. She pronounced it thigariyo like a foreigner. When she was a child she had lived in faraway places that she would take them to one day. She was warm-blooded, she said, not like their father who was a reptile. Their mother was clever and funny and surprising and nothing like their friends’ mothers. ‘Exotic’, their father said.

The argument about who smelled of what wasn’t over apparently because their mother picked up a blue-and-white-striped jug from the dresser and threw it at their father, who was sitting at the table staring at his typewriter as if the words would write themselves if he was patient enough. The jug hit him on the side of the head and he roared with shock and pain. With a speed that Joanna could only admire, Jessica plucked Joseph out of his high-chair and said, ‘Come on,’ to Joanna and they went upstairs where they tickled Joseph on the double bed that Joanna and Jessica shared. There was no heating in the bedroom and the bed was piled high with eiderdowns and old coats that belonged to their mother. Eventually all three of them fell asleep, nestled in the mingled scents of damp and mothballs and Je Reviens.

When Joanna woke up she found Jessica propped up on pillows, wearing gloves and a pair of earmuffs and one of the coats from the bed, drowning her like a tent. She was reading a book by torchlight.

‘Electricity’s off,’ she said, without taking her eyes off the book. On the other side of the wall they could hear the horrible animal noises that meant their parents were friends again. Jessica silently offered Joanna the earmuffs so that she didn’t have to listen.

When the spring finally came, instead of planting a vegetable garden, their father went back to London and lived with ‘his other woman’ — which was a big surprise to Joanna and Jessica, although not apparently to their mother. Their father’s other woman was called Martina — the poet — their mother spat out the word as if it was a curse. Their mother called the other woman (the poet) names that were so bad that when they dared to whisper them (bitch-cunt-whore-poet) to each other beneath the bedclothes they were like poison in the air.

Although now there was only one person in the marriage, their mother still didn’t paint.

They made their way along the lane in single file, ‘Indian file’, their mother said. The plastic shopping bags hung from the handles of the buggy and if their mother let go it tipped backwards on to the ground.

‘We must look like refugees,’ she said. ‘Yet we are not downhearted,’ she added cheerfully. They were going to move back into town at the end of the summer, ‘in time for school’.

‘Thank God,’ Jessica said, in just the same way their mother said it.

Joseph was asleep in the buggy, his mouth open, a faint rattle from his chest because he couldn’t shake off a summer cold. He was so hot that their mother stripped him to his nappy and Jessica blew on the thin ribs of his little body to cool him down until their mother said, ‘Don’t wake him.’

There was the tang of manure in the air and the smell of the musty grass and the cow parsley got inside Joanna’s nose and made her sneeze.

‘Bad luck,’ her mother said, ‘you’re the one that got my allergies.’ Their mother’s dark hair and pale skin went to her ‘beautiful boy’ Joseph, her green eyes and her ‘painter’s hands’ went to Jessica. Joanna got the allergies. Bad luck. Joseph and their mother shared a birthday too although Joseph hadn’t had any birthdays yet. In another week it would be his first. ‘That’s a special birthday,’ their mother said. Joanna thought all birthdays were special.

Their mother was wearing Joanna’s favourite dress, blue with a pattern of red strawberries. Their mother said it was old and next summer she would cut it up and make something for Joanna out of it if she liked. Joanna could see the muscles on her mother’s tanned legs moving as she pushed the buggy up the hill. She was strong. Their father said she was ‘fierce’. Joanna liked that word. Jessica was fierce too. Joseph was nothing yet. He was just a baby, fat and happy. He liked oatmeal and mashed banana, and the mobile of little paper birds their mother had made for him that hung above his cot. He liked being tickled by his sisters. He liked his sisters.

Joanna could feel sweat running down her back. Her worn cotton dress was sticking to her skin. The dress was a hand-me-down from Jessica. ‘Poor but honest,’ their mother laughed. Her big mouth turned down when she laughed so that she never seemed happy even when she was. Everything Joanna had was handed down from Jessica. It was as if without Jessica there would be no Joanna. Joanna filled the spaces Jessica left behind as she moved on.

Invisible on the other side of the hedge, a cow made a bellowing noise that made her jump. ‘It’s just a cow,’ her mother said.

‘Red Devons,’ Jessica said, even though she couldn’t see them. How did she know? She knew the names of everything, seen and unseen. Joanna wondered if she would ever know all the things that Jessica knew.

After you had walked along the lane for a while you came to a wooden gate with a stile. They couldn’t get the buggy through the stile so they had to open the gate. Jessica let the dog off the lead and he scrambled up and over the gate in the way that Jessica had taught him. The sign on the gate said ‘Please Close The Gate Behind You’. Jessica always ran ahead and undid the clasp and then they both pushed at the gate and swung on it as it opened. Their mother had to heave and shove at the buggy because all the winter mud had dried into deep awkward ruts that the wheels got stuck in. They swung on the gate to close it as well. Jessica checked the clasp. Sometimes they hung upside down on the gate and their hair reached the ground like brooms sweeping the dust and their mother said, ‘Don’t do that.’

The track bordered a field. ‘Wheat,’ Jessica said. The wheat was very high although not as high as the hedges in the lane. ‘They’ll be harvesting soon,’ their mother said. ‘Cutting it down,’ she added, for Joanna’s benefit. ‘Then we’ll sneeze and wheeze, the pair of

us.’ Joanna was already wheezing, she could hear the breath whistling in her chest.

The dog ran into the field and disappeared. A moment later he sprang out of the wheat again. Last week Joanna had followed the dog into the field and got lost and no one could find her for a long time. She could hear them calling her, moving further and further away. Nobody heard her when she called back. The dog found her.

They stopped halfway along and sat down on the grass at the side of the track, under the shady trees. Their mother took the plastic carrier bags off the buggy handles and from one of the bags brought out some little cartons of orange juice and a box of chocolate finger biscuits. The orange juice was warm and the chocolate biscuits had melted together. They gave some of the biscuits to the dog. Their mother laughed with her down-turned mouth and said, ‘God, what a mess,’ and looked in the baby-bag and found wipes for their chocolate-covered hands and mouths. When they lived in London they used to have proper picnics, loading up the boot of the car with a big wicker basket that had belonged to their mother’s mother who was rich but dead (which was just as well apparently because it meant she didn’t have to see her only daughter married to a selfish, fornicating waster). If their grandmother was rich why didn’t they have any money? ‘I eloped,’ their mother said. ‘I ran away to marry your father. It was very romantic. At the time. We had nothing.’

‘You had the picnic basket,’ Jessica said and their mother laughed and said, ‘You can be very funny, you know,’ and Jessica said, ‘I do know.’

From the Hardcover edition.

In the Past

Harvest

The heat rising up from the tarmac seemed to get trapped between the thick hedges that towered above their heads like battlements.

‘Oppressive,’ their mother said. They felt trapped too. ‘Like the maze at Hampton Court,’ their mother said. ‘Remember?’

‘Yes,’ Jessica said.

‘No,’ Joanna said.

‘You were just a baby,’ their mother said to Joanna. ‘Like Joseph is now.’ Jessica was eight, Joanna was six.

The little road (they always called it ‘the lane’) snaked one way and then another, so that you couldn’t see anything ahead of you. They had to keep the dog on the lead and stay close to the hedges in case a car ‘came out of nowhere’. Jessica was the eldest so she was the one who always got to hold the dog’s lead. She spent a lot of her time training the dog, ‘Heel!’ and ‘Sit!’ and ‘Come!’ Their mother said she wished Jessica was as obedient as the dog. Jessica was always the one who was in charge. Their mother said to Joanna, ‘It’s all right to have a mind of your own, you know. You should stick up for yourself, think for yourself,’ but Joanna didn’t want to think for herself.

The bus dropped them on the big road and then carried on to somewhere else. It was ‘a palaver’ getting them all off the bus. Their mother held Joseph under one arm like a parcel and with her other hand she struggled to open out his newfangled buggy. Jessica and Joanna shared the job of lifting the shopping off the bus. The dog saw to himself. ‘No one ever helps,’ their mother said. ‘Have you noticed that?’ They had.

‘Your father’s country fucking idyll,’ their mother said as the bus drove away in a blue haze of fumes and heat. ‘Don’t you swear,’ she added automatically, ‘I’m the only person allowed to swear.’

They didn’t have a car any more. Their father (‘the bastard’) had driven away in it. Their father wrote books, ‘novels’. He had taken one down from a shelf and shown it to Joanna, pointed out his photograph on the back cover and said, ‘That’s me,’ but she wasn’t allowed to read it, even though she was already a good reader. (‘Not yet, one day. I write for grown-ups, I’m afraid,’ he laughed. ‘There’s stuff in there, well . . .’)

Their father was called Howard Mason and their mother’s name was Gabrielle. Sometimes people got excited and smiled at their father and said, ‘Are you the Howard Mason?’ (Or sometimes, not smiling, ‘that Howard Mason’ which was different although Joanna wasn’t sure how.)

Their mother said that their father had uprooted them and planted them ‘in the middle of nowhere’. ‘Or Devon, as it’s commonly known,’ their father said. He said he needed ‘space to write’ and it would be good for all of them to be ‘in touch with nature’. ‘No television!’ he said as if that was something they would enjoy.

Joanna still missed her school and her friends and Wonder Woman and a house on a street that you could walk along to a shop where you could buy the Beano and a liquorice stick and choose from three different kinds of apples instead of having to walk along a lane and a road and take two buses and then do the same thing all over again in reverse.

The first thing their father did when they moved to Devon was to buy six red hens and a hive full of bees. He spent all autumn digging over the garden at the front of the house so it would be ‘ready for spring’. When it rained the garden turned to mud and the mud was trailed everywhere in the house, they even found it on their bed sheets. When winter came a fox ate the hens without them ever having laid an egg and the bees all froze to death which was unheard of, according to their father, who said he was going to put all those things in the book (‘the novel’) he was writing. ‘So that’s all right then,’ their mother said.

Their father wrote at the kitchen table because it was the only room in the house that was even the slightest bit warm, thanks to the huge temperamental Aga that their mother said was ‘going to be

the death of her’. ‘I should be so lucky,’ their father muttered. (His book wasn’t going well.) They were all under his feet, even their mother.

‘You smell of soot,’ their father said to their mother. ‘And cabbage and milk.’

‘And you smell of failure,’ their mother said.

Their mother used to smell of all kinds of interesting things, paint and turpentine and tobacco and the Je Reviens perfume that their father had been buying for her since she was seventeen years old and ‘a Catholic schoolgirl’, and which meant ‘I will return’ and was a message to her. Their mother was ‘a beauty’ according to their father but their mother said she was ‘a painter’, although she hadn’t painted anything since they moved to Devon. ‘No room for two creative talents in a marriage,’ she said in that way she had, raising her eyebrows while inhaling smoke from the little brown cigarillos she smoked. She pronounced it thigariyo like a foreigner. When she was a child she had lived in faraway places that she would take them to one day. She was warm-blooded, she said, not like their father who was a reptile. Their mother was clever and funny and surprising and nothing like their friends’ mothers. ‘Exotic’, their father said.

The argument about who smelled of what wasn’t over apparently because their mother picked up a blue-and-white-striped jug from the dresser and threw it at their father, who was sitting at the table staring at his typewriter as if the words would write themselves if he was patient enough. The jug hit him on the side of the head and he roared with shock and pain. With a speed that Joanna could only admire, Jessica plucked Joseph out of his high-chair and said, ‘Come on,’ to Joanna and they went upstairs where they tickled Joseph on the double bed that Joanna and Jessica shared. There was no heating in the bedroom and the bed was piled high with eiderdowns and old coats that belonged to their mother. Eventually all three of them fell asleep, nestled in the mingled scents of damp and mothballs and Je Reviens.

When Joanna woke up she found Jessica propped up on pillows, wearing gloves and a pair of earmuffs and one of the coats from the bed, drowning her like a tent. She was reading a book by torchlight.

‘Electricity’s off,’ she said, without taking her eyes off the book. On the other side of the wall they could hear the horrible animal noises that meant their parents were friends again. Jessica silently offered Joanna the earmuffs so that she didn’t have to listen.

When the spring finally came, instead of planting a vegetable garden, their father went back to London and lived with ‘his other woman’ — which was a big surprise to Joanna and Jessica, although not apparently to their mother. Their father’s other woman was called Martina — the poet — their mother spat out the word as if it was a curse. Their mother called the other woman (the poet) names that were so bad that when they dared to whisper them (bitch-cunt-whore-poet) to each other beneath the bedclothes they were like poison in the air.

Although now there was only one person in the marriage, their mother still didn’t paint.

They made their way along the lane in single file, ‘Indian file’, their mother said. The plastic shopping bags hung from the handles of the buggy and if their mother let go it tipped backwards on to the ground.

‘We must look like refugees,’ she said. ‘Yet we are not downhearted,’ she added cheerfully. They were going to move back into town at the end of the summer, ‘in time for school’.

‘Thank God,’ Jessica said, in just the same way their mother said it.

Joseph was asleep in the buggy, his mouth open, a faint rattle from his chest because he couldn’t shake off a summer cold. He was so hot that their mother stripped him to his nappy and Jessica blew on the thin ribs of his little body to cool him down until their mother said, ‘Don’t wake him.’

There was the tang of manure in the air and the smell of the musty grass and the cow parsley got inside Joanna’s nose and made her sneeze.

‘Bad luck,’ her mother said, ‘you’re the one that got my allergies.’ Their mother’s dark hair and pale skin went to her ‘beautiful boy’ Joseph, her green eyes and her ‘painter’s hands’ went to Jessica. Joanna got the allergies. Bad luck. Joseph and their mother shared a birthday too although Joseph hadn’t had any birthdays yet. In another week it would be his first. ‘That’s a special birthday,’ their mother said. Joanna thought all birthdays were special.

Their mother was wearing Joanna’s favourite dress, blue with a pattern of red strawberries. Their mother said it was old and next summer she would cut it up and make something for Joanna out of it if she liked. Joanna could see the muscles on her mother’s tanned legs moving as she pushed the buggy up the hill. She was strong. Their father said she was ‘fierce’. Joanna liked that word. Jessica was fierce too. Joseph was nothing yet. He was just a baby, fat and happy. He liked oatmeal and mashed banana, and the mobile of little paper birds their mother had made for him that hung above his cot. He liked being tickled by his sisters. He liked his sisters.

Joanna could feel sweat running down her back. Her worn cotton dress was sticking to her skin. The dress was a hand-me-down from Jessica. ‘Poor but honest,’ their mother laughed. Her big mouth turned down when she laughed so that she never seemed happy even when she was. Everything Joanna had was handed down from Jessica. It was as if without Jessica there would be no Joanna. Joanna filled the spaces Jessica left behind as she moved on.

Invisible on the other side of the hedge, a cow made a bellowing noise that made her jump. ‘It’s just a cow,’ her mother said.

‘Red Devons,’ Jessica said, even though she couldn’t see them. How did she know? She knew the names of everything, seen and unseen. Joanna wondered if she would ever know all the things that Jessica knew.

After you had walked along the lane for a while you came to a wooden gate with a stile. They couldn’t get the buggy through the stile so they had to open the gate. Jessica let the dog off the lead and he scrambled up and over the gate in the way that Jessica had taught him. The sign on the gate said ‘Please Close The Gate Behind You’. Jessica always ran ahead and undid the clasp and then they both pushed at the gate and swung on it as it opened. Their mother had to heave and shove at the buggy because all the winter mud had dried into deep awkward ruts that the wheels got stuck in. They swung on the gate to close it as well. Jessica checked the clasp. Sometimes they hung upside down on the gate and their hair reached the ground like brooms sweeping the dust and their mother said, ‘Don’t do that.’

The track bordered a field. ‘Wheat,’ Jessica said. The wheat was very high although not as high as the hedges in the lane. ‘They’ll be harvesting soon,’ their mother said. ‘Cutting it down,’ she added, for Joanna’s benefit. ‘Then we’ll sneeze and wheeze, the pair of

us.’ Joanna was already wheezing, she could hear the breath whistling in her chest.

The dog ran into the field and disappeared. A moment later he sprang out of the wheat again. Last week Joanna had followed the dog into the field and got lost and no one could find her for a long time. She could hear them calling her, moving further and further away. Nobody heard her when she called back. The dog found her.

They stopped halfway along and sat down on the grass at the side of the track, under the shady trees. Their mother took the plastic carrier bags off the buggy handles and from one of the bags brought out some little cartons of orange juice and a box of chocolate finger biscuits. The orange juice was warm and the chocolate biscuits had melted together. They gave some of the biscuits to the dog. Their mother laughed with her down-turned mouth and said, ‘God, what a mess,’ and looked in the baby-bag and found wipes for their chocolate-covered hands and mouths. When they lived in London they used to have proper picnics, loading up the boot of the car with a big wicker basket that had belonged to their mother’s mother who was rich but dead (which was just as well apparently because it meant she didn’t have to see her only daughter married to a selfish, fornicating waster). If their grandmother was rich why didn’t they have any money? ‘I eloped,’ their mother said. ‘I ran away to marry your father. It was very romantic. At the time. We had nothing.’

‘You had the picnic basket,’ Jessica said and their mother laughed and said, ‘You can be very funny, you know,’ and Jessica said, ‘I do know.’

From the Hardcover edition.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAnchor Canada

- Publication date2009

- ISBN 10 0385666837

- ISBN 13 9780385666831

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 30.24

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

When Will There Be Good News?

Published by

Anchor Canada

(2009)

ISBN 10: 0385666837

ISBN 13: 9780385666831

New

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0385666837-2-1

Buy New

US$ 30.24

Convert currency

When Will There Be Good News?

Published by

Anchor Canada

(2009)

ISBN 10: 0385666837

ISBN 13: 9780385666831

New

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0385666837-new

Buy New

US$ 30.27

Convert currency